What does it mean to be remembered? In around 360 years will someone be reading your words only because, by chance, a single page of your notes had a passing reference to some person, or event that history decided was “noteworthy”?

What if that is history’s only memory of you? Despite what you think is worth remembering? Do you care if your thoughts are remembered but you are not? Or if they are remembered but people are not sure if it was you who said them or someone else… your son, or maybe your father?

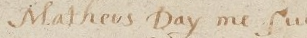

Around the early 1600s, either Matthew Day, or Matthew Day, wrote a utilitarian commonplace (you can find it here), in a satchel-sized, gold-embossed book…

Images and content of this post thanks to Folger Shakespeare Library. This post and images are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA 4.0).

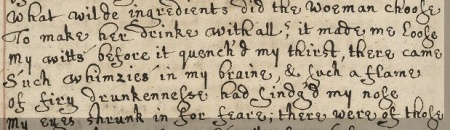

Day was fascinated by current events, poetry about love and relationships. Many of his verses have titles like “upon the fire upon London Bridge”, “Upon Cardinall Woolsey”, “Upon one Parsons, once organist at Westminster”.

Day seems to be the type of character who is just as comfortable around titled folk as he was at the local pub. While he copied down plenty of inspirational love poetry (just a sign of the times), his writing was just as careful when transcribing quirky verses like “Of one that kill’d himself by stopping his breath with a handkercheife”. In fact, after the Latin text and a poem about cupid’s bow, his commonplace book has a funny poem in honour of a (hopefully fictional) man killed in a pub by an empty beer tankard, and a poem in praise of tobacco.

… or this one. You can probably guess how the rest of this rhyme goes.

In some ways this commonplace is a workman’s tool. He copied poems and speeches verbatim, with margin notes and numbered paragraphs. Most of the text does not have a reference, so it is hard to tell what is his own writing. Probably most of it was copied quotes, although he did have a weakness for anagrams and wordplay.

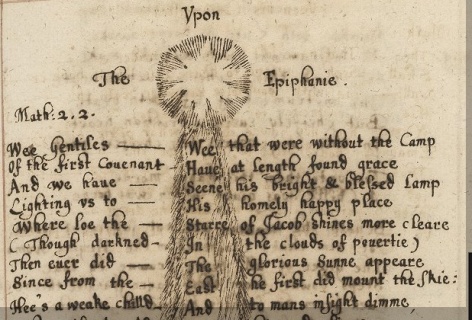

Latin aphorisms on the five senses. Or so I’m told.

Make a note if you know someone named “Judeth Sondes”

Buzzfeed: “Someone began writing biblical quotes. You won’t believe what happened next!”

Mr Matthew Day seems like someone you could have dinner with, swap thoughts about movements in the clergy and the government as well as some rude jokes and local gossip thrown in.

Day wrote a few, seemingly random words at the inside bottom corner of each left-hand page. It took me a little while to realise each of these were actually the first few words of the next page. You can imagine Day in front of a large audience, commonplace book in hand, confidently reciting a pithy and lengthy quote, and using these marks to guide his memory as his eye skims from the bottom of the page to the next. This is a personal commonplace, but one designed to be used in public.

According to the Folger Shakespeare Library, Mr Matthew Day was born in 1574, which makes him 76 at the time of the commonplace book (1650). Day was five-time Mayor of Windsor. He had twelve children with his wife Mary Dowdeswell and died in 1661. He has a mural in the Church of St John the Baptist in Windsor.

According to Tom Cain and Ruth Connolly in “The Complete Poetry of Robert Herrick, Volume 2“, Matthew Day was born in 1605, the eldest son of Matthew Day and Mary Dowdeswell, which makes him 45 at the time of the commonplace book. He was a ‘Church of England clergyman and biblical commentator‘ who was a fellow of King’s College Cambridge until 1643 and died in 1684.

When I first started reading the commonplace, I had in mind the five-time Mayor. This was a man whose life was built around befriending locals, royals and commonpeople alike. Who best to bowl out a bawdy verse (or a clever anagram poem) in a pub, then hop in his coach for a quick chat about the new Cardinal before giving a formal speech on a virtuous life?

Then, after reading Cain and Connolly’s comments, I had a view of a busy student, given a commonplace book as a gift that he used to transcribe some Latin studies during university. He started in earnest, even copying the text into an index at the back, but after only a short time he left the book on a shelf. He took it out every now and then, his handwriting changing over the years, and copies down funny poems, dabbles in anagrams – maybe about some of the women he is thinking about. Once he begins his religious career his writing becomes more formal. He starts using the book for his sermons and his personal study.

The text doesn’t give many clues and Cain and Connolly say the handwriting analysis (by ‘Mary Hobbs’) was “equivocal”. You could argue the topics would appeal both to a young up-and-coming preacher and a career politician. The one section that is not in verse (apart from some anagram notes) is a note, copied on page 27, from ‘Th. Dekker’ entitled ‘Noble Sr’. Maybe this relates to a Thomas Dekker (1572-1632) who wrote the play “The Noble Spanish Soldier” in 1622. If so, maybe the best explanation is a personal note from one ageing peer to another. Or maybe the explanation is that it was friendly note to a child of one of Dekker’s long-time friends?

Which is the right one? And, 360 years on, does it matter? How long would you wait until you would be happy for your thoughts, your actions to be merged with that of your son or your father, or disappear altogether?

Does it matter? This particular commonplace book was owned for some time by John Payne Collier before it found its way to the Folger library.

If you look up John Payne Collier on Wikipedia, you will find he was “an English Shakespearean critic and forger”, responsible in some way for some of the most controversial forgeries in Shakespearean history. Or not, depending on which scholar you believe, because according to Wikipedia some of his writings were taken out of context, and the verdict is still out on whether he was a forger (or to what degree).

So what do we have? Words on a page. Selected words that a man named Matthew Day found important enough to copy down, to carry with him, to remember. Words that he used like clothing in his life and career to present himself in a certain way to the people he spent his life serving. They are just words, and father and son have melded together in history.

And if someone did find evidence – some date or comment in the book, or some other piece of handwriting that definitively proved it was one Matthew Day or the other, where are we now? Is it interesting at all? After all, this is not Shakespeare we are talking about, as John Payne Collier would no doubt say. Because if someone’s life was touched by Mr Shakespeare then the true source of that particular material is important. Isn’t it?

Is it?

But this commonplace is only one man – well in fact two men – both dedicated and successful in their community in their own way but ‘unimportant’ in history. They did not add anything much to posterity apart from a mural, some dusty records somewhere and a commonplace book that can be read in Windsor, or online from the other side of the world.

Thank you Mr Day.

-*-

The Folger Shakespeare Library has a huge digital archive. Their interface is easy to use, the scans are stunning and, best of all, much of the material is online under a Creative Commons license.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License