When you read a transcription instead of the original written page, how much of the meaning do you lose? And how much of the magic?

The article hooked me with its by-line, which is basically the reason for my own blog.

“A [commonplace book] often tells us more, unwittingly, about its compiler than a self-description would.”

Basically – historical letters and (most) diaries are self-curated, a type of manual Facebook. While you can look at other ephemera – scrapbooks, professional notebooks, marginalia – these resources focus on a small range of topics. Commonplace books are a catch-all for what the creator thought was worth remembering. Therefore, it is the curation, the time and care spent in the record, and the formatting of the book that is just as important as the text itself.

The main topic of Parris’ article is “More Rags of Time”, the limited edition, printed commonplace book of Kenneth (Lord) Baker (now only available

through specialist booksellers).

The book appears to be mainly a collection of transcribed quotes, with the odd quote from Lord Baker (“It is no good telling me that there are bad aunts and good aunts. At the core, they are all alike. Sooner or later, out pops the cloven hoof”).

Parris delves into the subject by talking about Baker’s notes showing “a lovely sense of self-mockery, a small dash of vanity, and a keen critical appreciation of satire”.

I completely agree with Parris that the commonplace book is a ‘lost art’ that is well deserving of revival. On the other hand, I have the nagging thought that a transcribed “commonplace book” – such as you see cropping up every now and then – somewhat misses the picture.

At most, these kind of books give a summary of the author’s likes and dislikes from borrowed text. That is where the magic – in my opinion – is lost.

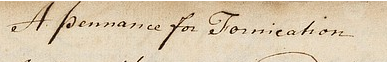

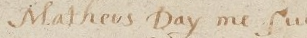

More than a journal or a diary, commonplace books were meant to be carried and used. It is one thing to read the quotes that someone decided to copy into their book. It is another to see the frayed edges of certain well-thumbed pages, to see the quotes that were scrawled compared with those carefully transcribed.

Some commonplace books have an index a-la Locke. Some have folded pages, crossed out quotes (once used by the author at a dinner party or book?), text running lengthwise, across the seam, in the margin, vertically or in a box.

Was a comment clustered in with others of the same type, or did an author dedicate an entire page of precious paper to the thought? How does the handwriting change over time, and does the marginalia point to the author reviewing and revising the original text years later?

All of these are also clues to the mind of the owner. Just as much as the choice of words. How much would we lose the magic of Da Vinci’s notebooks if we saw only the printed text and some cropped images?

There are many amazing, digitally scanned collections of commonplace books online – check out my

reference page for more links. Yes, the handwriting is often hard work and for an amateur like me much of it is almost unreadable. But half the fun of looking at these books is getting to know the author through their own pen scratches rather than a neatly typed and bound book. It’s a lot of effort and many people won’t have the patience, but lets be honest – the printed versions aren’t exactly flying off the shelves in the Top Sellers section of the bookshop!